2025-03-04

•Sam Reed

Hammer the Aigles

What does it mean to beat the odds anyways?

Author’s Note

Please note that running a startup satiates my personal appetite for risk taking. Consider my reflections on sports betting to be the words of an interested outsider instead of an active practitioner.

🍅 🍅 🍅

What does it mean to “Beat the odds” anyways?

We’ve all said it:

How a rag-tag band of colonists beat the odds in the fight for America.

An underprivileged kid beat the odds and rose to the heights of high finance. Here’s how she’s giving back.

I beat the odds and survived. Every day feels like a blessing.

The expression is a time machine: its function is to take us back to the point in time before hindsight proved our expectations wrong. It’s a friendly, concise idiom whose job is to remind us that the future doesn’t always take the most likely path.

It also signifies victory. Saying “He beat the odds and caught his flight” doesn’t simply mean that an unlikely event transpired—it also means that someone challenged the odds and emerged as a victor. Hoorah, champ.

In May of 2018, the US Supreme Court struck down the Amateur Sports Protection Act, paving the way for state governments to legalize online sports betting. Since then, beating the odds has become a sport within sports. It’s widely known that the major online sportsbooks and casinos employ large technical teams to help crunch data and make highly accurate projections, but could the arrival of widely available AI models help the little guy(s) become better bettors?

Beating the books

Let’s pretend it’s a Friday night in New York City and you’re at home on the couch because you’re 30 now and can’t throw ‘em back like you used to.

Though you’re respecting your body’s call for a change of pace, it’s been a long week at the office and you feel you’ve earned at least an hour or two of indulgence.

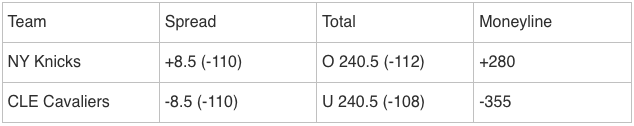

You pull out your phone and pop open the DraftKings app. You see the following bets for tonight’s Knicks game:

Aha, just what the doctor ordered. Now time to pick a wager. What does your thought process look like? Is it anything like this?

The Knicks only lost by six last time these two teams played and they were struggling back then. Cleveland has been amazing this year but the Knicks are still a top four scoring team. We’re weaker on defense but 8.5 points seems too high for this offense not to cover. Give me the road ‘dogs. [1]

If so, you should know that even though this is definitely better than nothing, it omits a foundational dimension of the game that you’re playing.

The problem with this line of thinking—which, by the way, the user interfaces of the betting apps seem to encourage—is that it begins with a focus on the binary event outcome (whether the Knicks will [0: win] or [1: lose] the game after adjusting their score upwards by 8.5 points) instead of first considering the odds (often displayed as the payout). This approach might still work for some people, but the mental model of the binary event outcome is not well-aligned with the markets that bettors are actually participating in.

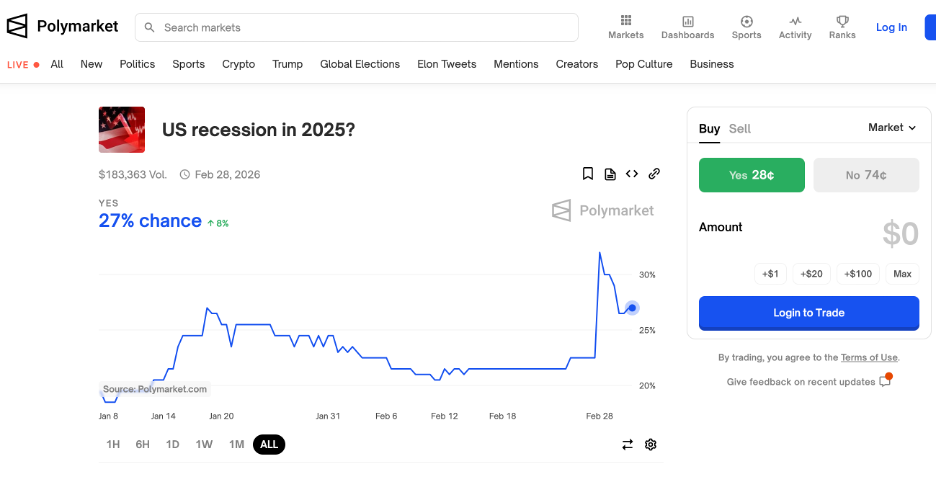

Bettors would be wise to instead think of each “Game” as a platform for many individual prediction markets (think: each independent “Line” that you see is its own prediction market) and then to think of each market’s value as a real-time measure of the probability (i.e. the odds) of the underlying event occurring. Keeping with the example above, the “Market” is trying to predict whether the Knicks will finish within 8.5 points of the Cavaliers, and the live value of this prediction (i.e. the probability of the event occurring) is a 52.38% likelihood (52.38% is the probability that a -110 payout implies). Some platforms, such as Polymarket, the cryptocurrency-based prediction market platform that rose to notoriety after outperforming election polls in the 2024 US presidential election, do a better job at making it clear that participants are engaged in an odds-based competition:

The essential mechanism that makes all of this true is the payout. An even payout (bet $50 to win $50) implies that an event has a 50-50 chance of happening because otherwise one counterparty would be guaranteed to lose money when taking a large series of these bets and therefore would rationally not participate. The implied odds adjust from there—again, when you see a -110 payout (which means that you bet $110 to win $100), it implies a ~52% probability of the underlying event happening, because if an event with this payout scheme had a lower probability of occurring, you’d be guaranteed to lose money by taking it over the long run. Therefore, if you see a bet marked at a -110 payout but you know that it actually has a 53% chance of occurring, this represents a positive expected value for you, because a win pays you a higher amount than what it would in a perfectly even contest. In theory if you find and take these bets over time, you’ll beat the sportsbooks. What’s it gonna be, Aspen or Vail?

Thinking in this way unearths the real competition: when you make a bet, you’re making a statement that the odds you see for an individual line (prediction market) are incorrect. You’re wagering that your measure of the odds is better than theirs. You’re trying to beat the odds.

Flip it

The lowly coin flip helps elucidate these ideas—let’s talk through it quickly before moving on.

If pulled a quarter out of my pocket and looked at you and said “I’ll pay you $20 if you win, but you pay me $10 if I win,” would you take it? Maybe not, because it’s just one flip and anything can happen. But what if I offered you the same bet a thousand times? Is your first thought about my flip height, whether the tails side is chipped, or the unique aerodynamics of a Maine state quarter? These might be things worth considering before accepting my final offer, but I’d wager that your first thought is about the fancy dinner I’m about to buy you for offering a +200 payout on a 50-50 bet.

The probability of sports outcomes obviously can’t be assessed as easily as coin flips. When you take on the betting markets, it’s you versus the consensus opinion, one that starts with computers and algorithms and data and gets adjusted by the skin-in-the-game participation of individual bettors. It’s an uphill battle from the start. Does your knowledge of sports count for anything when competing against Mr. Market, or is all hope lost?

The lowly coin flip helps elucidate these ideas—let’s talk through it quickly before moving on.

If pulled a quarter out of my pocket and looked at you and said “I’ll pay you $20 if you win, but you pay me $10 if I win,” would you take it? Maybe not, because it’s just one flip and anything can happen. But what if I offered you the same bet a thousand times? Is your first thought about my flip height, whether the tails side is chipped, or the unique aerodynamics of a Maine state quarter? These might be things worth considering before accepting my final offer, but I’d wager that your first thought is about the fancy dinner I’m about to buy you for offering a +200 payout on a 50-50 bet.

The probability of sports outcomes obviously can’t be assessed as easily as coin flips. When you take on the betting markets, it’s you versus the consensus opinion, one that starts with computers and algorithms and data and gets adjusted by the skin-in-the-game participation of individual bettors. It’s an uphill battle from the start. Does your knowledge of sports count for anything when competing against Mr. Market, or is all hope lost?

Can’t we all just disagree?

Something that makes it nearly impossible to make the mindset shift outlined above is that the tools for making accurate forecasts, such as computer-based statistical models and a robust historical dataset, simply aren’t available to most people.

Given the lack of ability for most people to make any sort of model-based calculation, casual bettors tend to rely on some combination of 1) pure intuition and 2) expert advice. These options lead to two obvious problems: the first being that no real system of analysis is employed, and the second being the skepticism that should be directed towards people who sell “Expert” advice instead of just acting on it and profiting for themselves.

With that said, many bettors are also fans of the sports on which they speculate, so they do bring a lot of knowledge to the table that could be useful in helping to establish probabilities. If these individuals could be combined into groups with other enthusiasts with a goal of arriving at a good sense of the odds for an individual contest via debate, could this help people arrive at better decisions?

Unanimous AI seems to believe in this future. Here’s a quote from theirblog post about how their AI-facilitated debate platform was used to pick the Eagles to win Super Bowl LIX, with a “Conviction score”of 55%:

At Unanimous AI, we don’t replace people with AI, we connect human groups together into super-intelligent systems. It’s a tradition to use our technology to predict high-profile events. This started back in 2016 when a CBS reporter challenged us to predict the Kentucky Derby, not just the winner but the first four horses in order. We did it, beating 540-1 odds: Newsweek Article 2016

Our technology has advanced significantly since 2016. Our latest platform, Thinkscape, enables large groups (up to 400 people) to hold real-time deliberative conversations that converge on optimized decisions, predictions, assessments, and estimations. And because it’s conversational, Thinkscape generates detailed qualitative insights why the group converged the way they did.

So… who WILL WIN the Super Bowl this year?

We were challenged by a reporter (Chuck Martin) to make the prediction by amplifying the collective intelligence of 104 members of the general public. This produced a reasonably strong forecast that the Philadelphia Eagles will win the Super Bowl. This goes against Open AI, Deepseek, and Gemini which all predicted Kansas City.

It’s important to note that Unanimous’ post came out before the Superbowl was played. There’s a fascinating video embedded in the blog post that discusses their process in more detail that’s worth watching if you have a spare minute.

Based on Unanimous’ write up, it sounds like AI wasn’t really doing the predicting at all, but instead was used to facilitate debate among 104 members of the general public and then to aggregate the results into a Unanimous proprietary “Conviction score.”

This is different! My guess is that most readers, especially readers that have spent time doing any sort of predictive modeling work, were thinking that I was about to talk about an AI model now widely accessible to the public that is going to spit out highly accurate gambling probabilities. That would be cool too—it might be more directly helpful to many people—but what makes this so fascinating is the way in which it opens the door for using Large Language Models to facilitate novel methods for calculating probabilities for real-world events.

Holding Court

I’m not a mathematician or probability expert, but I’ve spent enough time engaging with the relevant material to know that there’s a deeply philosophical nature to the topic of probability in the real world. This is because in the real world, though it’s obviously possible to calculate meaningful odds, many events don’t have precise intrinsic probabilities. Even if you subscribe to the strange ideas of thinkers like Robert Sapolksy about life being completely deterministic, it’s still hard to imagine that in such a universe we humans would be able to create a prediction model of such Godlike omniscience to nullify the value of forecasting altogether (spoiler alert – you can watch this Fx show for an exploration of the idea). The emergent properties of complex systems, combined with a dose of free will (real or felt), leave real world risk takers with no sharper tools than approximation.

If we take a step back from the competition within prediction markets and analyze them as a whole, it becomes clear that prediction markets (such as sports betting exchanges) in aggregate are a beautifully innovative mechanism for approximating real-world odds. These markets are an aggregation of the opinions of many people, and because they involve a financial risk and reward, participants have a strong incentive to be right. They are the epitome of “Put your money where your mouth is” and have shown to be accurate over time.

The approach that Unanimous described above, the facilitation of small group debate on a large scale, feels like a fundamentally new mechanism for calculating real-world odds. It might not work—the experiment will need to be run many more times and with a much larger number of individuals before being taken seriously—but large language models combined with other AI techniques like sentiment scoring at least open this up as a more feasible experiment than would have been possible before today.

The expense of paying individual debate moderators on a mass scale would be high. Training each moderator to facilitate debates in a trustworthy way would be a challenge. Having participants fill out static forms would remove the debate-like aspect. Artificial intelligence finally provides the scalable, repetitive cognition necessary to make this possible.

There are plenty of problems with this approach, the biggest one being that all that comes out at the end is a “Conviction score” and no one really knows how well that will correlate with real results over time. But…at the end of the day…what are things like Polymarket or sports betting markets other than measures of mass conviction? This experiment feels worth running.

See you next week!

Citations [1] https://www.actionnetwork.com/nba/knicks-vs-cavaliers-prediction-odds-parlay-pick-for-friday-february-21-qs